THE BEAN IDENTITY

There are more than five hundred genera and about six thousand species in the Rubiaceae family; one of these is Coffea. Although botanists regard all seed-bearing plants that are part of the Rubiaceae family as coffee trees, the coffee trade is mainly concerned with just two species.

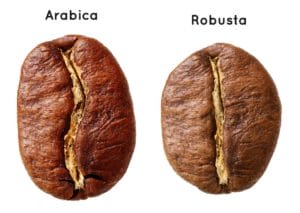

The coffee species of overwhelming importance are Coffea Arabica and Coffea Canephora. In general terms, coffee is divided into two main types, Arabica and Robusta, but botanically speaking, Arabica has two main varieties, Typica and Bourbon, and the most common form of Canephora is the variety Robusta.

However, even within a single varietal of coffee, different and often unpredictable growing conditions and process methods will produce a varying flavour profile in the resulting cup, and a successful coffee bean may exhibit a completely distinct set of characteristics when grown in one location as compared to another. A prime example of this is Kona, the name reserved for Arabica beans grown only in the Kona district of Hawaii, because the specific environment gives the beans unique qualities that are not exhibited when grown elsewhere.

ARABICA COFFEE

Despite containing less caffeine than Robusta coffee beans, Arabica coffee beans are considered superior in taste. Arabica tends to have a smoother, sweeter taste, with tones of chocolate or sugar, and often fruits or berries. Robusta, on the other hand, has a stronger, harsher and more bitter taste, with grainy or rubbery tones.

According to the International Coffee Organisation, more than 60 percent of world coffee production comes from Arabica cultivars. This was the type of bean that started off the whole coffee story in Ethiopia, and it still grows best in higher elevatinos. The glorious-smelling flowers appear after a couple of years and produce ellipsoidal fruits, inside which are usually two flat seeds or coffee beans. The shrub can grow to 15 feet (5m), but to make it more commercially viable, it is usually pruned to about 6 feet (2m). Arabica has two sets of chromosomes, so it is capable of self-pollination, which means that its forms generally remain fairly stable because cross-pollination is less probable.

Of the two most common varieties of Coffea Arabica, Typica, was the first variety of the species to be discovered and, therefore, is regarded as the original coffee of the New World. It is a low-yielding variety that is valued for its excellent cup quality.

Bourbon varieties are often prized for their complex, balanced aromas and have spawned many high-quality mutations and subtypes, such as the natural mutations of Caturra, San Ramon, and Pacas. There are also a number of Bourbon cultivars that have been propagated to suit the regional climate, environment, and elevation, such as the prized Blue Mountain varieties, which only flourish at high altitudes. Other examples include Mundo Novo and Yellow Bourbon.

ROBUSTA COFFEE

Robusta is the most common varietal of Coffea Canephora, Arabica’s more street-smart younger brother. Despite its flavour being considered less refined, Robusta is sometimes used in espresso blends, because it is known for producing a better crema — the creamy layer found on top of an espresso shot —than Arabica, and it is hardier and more resistant to disease, especially coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix). It also produces better yields and packs more caffeine. It is thought that the amplified caffeine content of Robusta, along with that of chlorogenic acids — naturally occurring antioxidants — is a result of the plant’s self-protection mechanism in warding off pests and disease. When present at low levels, chlorogenic acids are considered an important part of a coffee’s flavour profile. However, Robusta contains higher levels of these acids than other coffee species, and some studies show that oxidation products generated by these acids can introduce off-flavours, potentially compromising cup quality.1

Growing well at lower altitudes, Robusta thrives in areas where Arabica would be devastated by fungus and other diseases and pests. A stouter plant than Arabica and about twice the size, it grows well at higher humidity. After flowering, the berries take almost a year to ripen. The Robusta is self-sterile; therefore, cross-pollination by wind and bees and other insects is necessary for the plant to reproduce.

Although Robusta is a varietal and not a coffee species in itself — as in the case of Arabica — there are a number of subtypes of the Robusta bean, with each exhibiting a unique set of characteristics, such as greater immunity to disease and increased production capacity in comparison to Arabica.